Back when I shared my brachioradialis recovery process with you, I also mentioned I’d been experiencing anterior hip pain. I’m now completely free from that pain, and wanted to discuss a bit about what I learned. Here I won’t be sharing any specific rehab protocols or corrective exercises, because there weren’t any. I’ll get to that. But in any case I think many of you will make use of these insights.

Capsular Conundrum

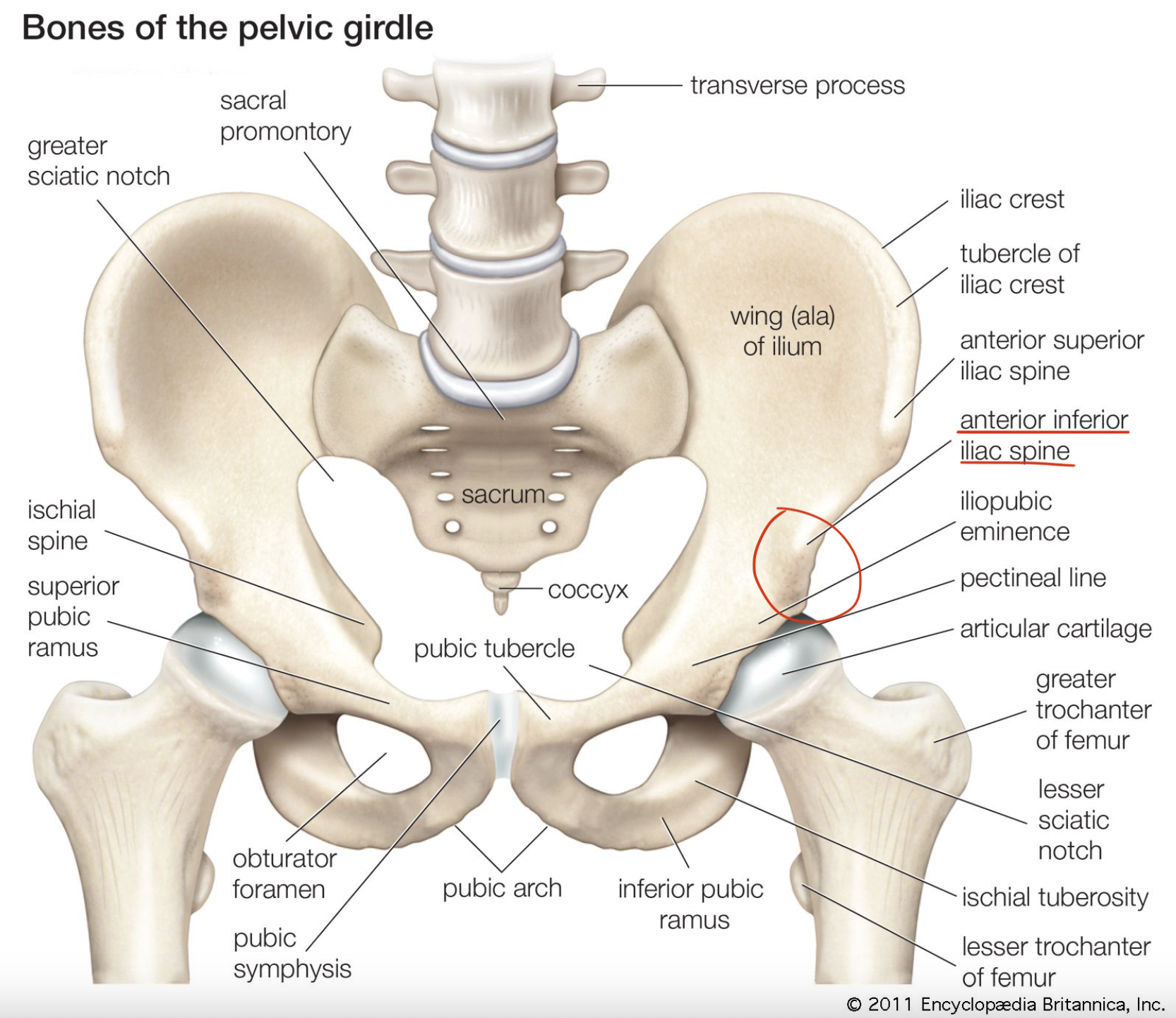

One day after a squat session about 11 months ago I began to feel pain in my anterior right hip, on and below the little protrusion of the anterior inferior iliac spine. It was not only painful during movements, but also to the touch.This happened suddenly, but not directly after the session. It was two days before the pain began to manifest.

At the time I was confused, and couldn’t quite attribute the pain to anything specific. I only knew both front and back squats seemed to aggravate it. Initially it wasn’t so painful that it stopped me from squatting, or held me back significantly from performance. After some squat sessions it would feel a little better, and after others it would get worse. So I couldn’t exactly be sure the squats were the cause or the pain trigger. Over time I noticed I began to compensate to avoid the pain during squats. And after about two months I recognized that it wasn’t going to resolve on its own. So I began to take active steps to recover.

What Didn’t Work

The symptoms seemed very consistent with anterior hip ‘impingement’—in other words, when hard structure runs into hard structure in the front of the hip and causes pain. I also considered it might be a strained hip flexor. So one by one I tried a number of things.

I tried strengthening external hip rotation via seated isometrics. I tried single-legged airplanes (stand on one foot with the torso level with the floor and other leg straight behind, rotating the non-standing hip upward and turning the torso to the side). I tried releasing and strengthening my adductors. I tried massage and manual release of the pain area. I tried strengthening my hip flexor front half kneel in its longest position. And nothing helped. In fact some of these made it worse—most notably the single-legged airplanes and massage.

The Culprit and Cure

After months of trial and error, I recognized once again that the issue wasn’t resolving. So in a moment of sobriety, I sat down and scoured my training notes and reviewed my training videos [an advantage of journaling and logging training with both written notes and video]. And when I did this I remembered something very specific about the squat session before the first occurrence of the hip pain: I had significantly widened my stance.

I remembered having consciously made this decision after studying the squat technique of Toshiki Yamamoto, one of the best olympic back squatters in the world, and how his very wide stance enabled him to stay exceptionally upright in his back squats. Naively fixated on the outward appearance of the technique, I tried to mimic this—thinking it was a just simple mechanical matter of leverages. It wasn’t.

I didn’t step quite as wide as Yamamoto-san, so I figured it would be alright. But this was still a significant adjustment for me in both front and back squat—especially considering my stance had been relatively more narrow than average prior to that day. I went from relatively narrow to relatively wide overnight, AND continued with the same loads, sets, and reps I’d been accustomed to all along. This stood out to me as the potential culprit of the hip pain, and nothing else had seemed to address the issue.

On that day, I went back to my relatively narrow stance. I did no further ‘corrective exercise’ or manual therapy. Within just a few weeks the pain that had plagued me for months had nearly gone. In another three weeks it was like it had never been there.

A Few Takeaways

1. Mind abrupt changes.

Sudden shifts in one or more variables is risky when using heavy loads at high effort. Even something seemingly trivial, when under this much stress, can become something very significant. It’s better to step back and integrate changes slowly and with great attention to feedback. Since then, for example, I’ve winded my stance a little. It’s not nearly as wide as it was when I first tried to force this change, but it’s a little wider. Instead of trying to bully my body into conforming to some abstract technical execution, I asked with each small adjustment, “How did that feel? How was the balance of weight? How engaged did the hips feel? Did I lose connection with my quads?” etc. And I would check this experience against a narrower stance multiple times, to test if my perception had been skewed.

2. Keep a record for reference.

A training log is very useful. If nothing else, it allows us a level of objectivity that otherwise wouldn’t be possible. It enables us to zoom out, look at macro trends, and free ourselves from the typical myopia that characterizes most experience. Training can be very personal, and very emotional. I came away from this experience with a new appreciation for [reasonably] detailed training logs, and reminded of my own inevitable folly. And it was at this time that I started keeping a daily written log of physical practice, even activities and significant emotional events on rest days. I refer back to it often, and it provides me with excellent feedback when making important strategic decisions.

3. I am not Toshiki Yamamoto.

And neither are you. I have this body, and that’s it, and that’s all. Trying to be Toshiki Yamamoto was a clear symptom of a deeper pattern of mine that appears in other spheres of my life. I noticed a tendency to cram myself into an abstract construct I thought would be better. And this was driven by a deeper narrative: “there is something wrong with the way I move, my body is somehow inherently weak and ugly in its movements.” What follows is a desire to ‘fix’ my movement from the outside by forcing constraints upon it.

Perhaps even more importantly, I understand from more than a decade of introspective practice that these patterns don’t just vanish when they are ‘understood.’ Seeing them is not enough. Because they will arise again. So instead of thinking I’ve ‘figured it out,’ I take this information with me. It helps me be aware of typical shortcomings I can expect to arise again in the future, so I might spot them faster and spend less time in dysfunction.

~ Devin